2017 Memorial Tournament Honoree: Climbing The Eternal Ladder

Always challenging himself to do greater things, Greg Norman continues to reach for the top long after he left behind his Hall-of-Fame playing career

Greg Norman is a 62-year-old grandfather.

He hasn’t played in an official tournament since the 2012 Senior Open Championship. He carries the battle scars of 13 surgeries, not to mention the scars from misfortunes like losing all four major championships in playoffs.

On the other hand, he leads the Greg Norman Company, which operates 17 profitable ventures ranging from course design and real estate development to turf research to sales of apparel, wine, eyewear and steaks. He puts more than 500,000 miles a year on his Gulfstream V, spanning the globe for business and pleasure. He’s giving some serious thought to climbing Mt. Everest.

Don’t worry, the Shark still attacks life. He even attacks rest.

Ostensibly, that’s what he’s doing when he’s home on his eight-acre estate on Jupiter Island, Fla., a verdant paradise featuring understated architectural elegance within the borders of the Intracoastal Waterway to the west and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Norman named the sanctuary “Tranquility,” but when he’s not somewhere else on earth, it’s another place to hit it hard. Six days a week, he puts in a two-hour workout in his state-of-the-art gym. Depending on which mastery urge strikes him, he’ll chase self-improvement in tennis, scuba diving, marlin fishing and even—rolling back the years to teenage days catching waves at famed Noosa Heads on Australia’s Sunshine Coast—surfing. The restlessness can backfire. Three years ago, Norman was trimming an unruly banyan tree when his chainsaw slipped and nearly severed his left arm at the wrist. After surgery, Norman was lucky to escape with only minor nerve damage.

“Anytime I’ve ever seen Greg do anything, he goes all in, all out,” says Geoff Ogilvy, who got to know his boyhood idol when Norman captained the International Team in the President Cups of 2009 and 2011 and hosted the players at his 11,60 0acre Seven Lakes ranch in Colorado. “No surprise he was an expert at fly-fishing and skeet-shooting and looked like John Wayne on a horse,” says Ogilvy. “Living at Greg’s pace those few days, I’d go to bed each night satisfied that what I did today was all I could do.”

These days, Norman devotes his main energy and focus to his growing company. Since his distinctive shark logo was introduced in 1989 while under contract with Reebok, he has become arguably the most successful athlete-turned-entrepreneur in history. On corporate retreats he speaks of the company’s “12-year horizon” and “200-year horizon,” because he wants his 50-some employees to share his vision for a brand that will stay relevant and endure beyond his lifetime. When he calls his 90-year-old father, Merv, in Brisbane, Australia, the elder Norman usually opens the conversation with “How’s the empire?”

At Tranquility, the emperor’s clothes are usually a tee shirt and shorts, but it doesn’t diminish the presence that for so many years popped off the television screen. As Norman strides down an elegant hallway to greet a visitor, the pale blue eyes still pierce, the hair is still flaxen and the face has retained its chiseled features. If anything, Norman seems more muscular and bronzed than during his playing days. Doubters can check him out on Instagram, along with the bronze bust of himself–commissioned by his wife, Kirsten, an interior designer—that now sits in his home office.

Norman moves through bright rooms accented with modern art, under a portico-covered courtyard adjacent to his 50-foot pool, to his Polynesian-style grill house, where the cool air under dark timbers evokes a temple-like feel. “Have had some good talks here,” he says, gesturing toward the slate table where guests from Bill Clinton to the late Seve Ballesteros to Rob O’Neill, the Seal Team 6 member who shot Osama Bin Laden, have rested their elbows.

Before sitting down, Norman points out two rows of towering palms at the bottom of the property, a paean to the original carriage way that existed before the island became the relaxing refuge for Vanderbilts, Rockefellers and Fords in the first half of the 20th century. In 1991 he was living about 20 miles south in Lost Tree Village in North Palm Beach, when his neighbor, Jack Nicklaus, told him about a special oceanfront property that a friend was putting on the market. “I drove up, saw it and bought it that afternoon for $4.9 million,” says Norman. Today it’s priced at $55 million.

It was one of the several times Nicklaus would help shape Norman’s life, most recently by giving him the news that the two-time winner of the Memorial Tournament presented by Nationwide had been chosen the 2017 Tournament Honoree.

“Jack has always been there for me,” says Norman. “When I started playing golf in 1971, I watched him on television in every major championship, right through his best years until I rst met him in 1976. I was always following his game to re ne my own game, and then following him for what he did in the business world. at roadmap, along with the friendship with him and his kids, has gone on for more than 40 years, which makes it very meaningful to receive Jack’s award.”

Waxing nostalgic puts Norman in a suitably reflective mood as he leans back in a rustic wooden chair, ruminating on his particular yin and yang.

On one hand, he parlayed physical talent with an aggressive and self-trusting mindset developed as a nature boy free-diving in the supercharged ecosystem of the Great Barrier Reef. Sharks were ever present in the ocean, and recounting his close encounters with Great Whites to the press at his first Masters in 1981 was how Norman got his nickname. “I got to know their behavior, so that I could deal with an individual fish, even the Oceanic White Tip [known as the “Dark Knight of the Ocean”], mano a mano,” Norman says evenly. Sensing that last phrase would require some explanation, he adds, “When a shark feels some kind of metal object, which gives off a little electricity in salt water, they take off like a scalded cat.”

Winning such staredowns bred a deep inner confidence. “My youth in the ocean, where I didn’t fear the unknown, made me into the golfer that I became,” he said in a Golf Digest profile in 2011. “Every time I jumped in, I was in exploratory mode. So with golf, I just went, ‘Golf, I love golf, I think I’m pretty good at it. OK, I’m going to try and be the best I can.’ Then all of a sudden, bam! There was no barrier in my mind about getting better and better and better.”

The ocean also gave Norman a surfer’s physique, and he employed the broad shoulders and dynamic balance to produce incredible club head speed, which was clocked at 130 mph in the late ’70s. As Lee Trevino once observed, “Norman makes the rest of us look like we’re hitting tennis balls.”

Rather than temper his power, Norman, in effect, doubled down, certain that he could remain accurate. Ogilvy, who grew up next to Royal Melbourne and watched Norman compete there several times, vividly remembers the reckless abandon with which his hero played. “Driver every hole, and driver off the deck into par 5s,” Ogilvy says. “Drivers on holes where no one else hit driver. Full swinging, leaving nothing on the table, 300 yards down narrow fairways with a persimmon driver and the old, spinny ball. No one else in that time had that gear. It’s diffcult to imagine that anyone has ever been that far ahead of his peers off the tee, which has to make Greg the best driver ever.”

“Greg was basically playing a di erent game,” says Lanny Wadkins, who played many practice rounds with Norman. “His gift for driving the ball very long and very straight, and especially on major-style set ups, that gave him a huge advantage over the rest of us.”

Norman knew it. “I would hit driver when other guys laid up,” he says. “The persimmon driver I used for years—a MacGregor Tommy Armour 693 [which Nicklaus also used]—you had to hit it solid or it wouldn’t really go, not like today’s clubs. My swing speed in the late 1970s, with a 43 1/4 inches long, X400 steel shaft, was clocked at between 128 and 132 mph. With a lighter, longer club and a more rebounding club face, I’d hit it 330 or 340 yards with that swing now, and straighter than I used to. Some of today’s guys hit it that long, but not many straight.”

Such aggression was Norman’s yin. But the yang was a strong methodical streak. Norman didn’t end up a beach bum because he intuitively understood—perhaps from the example of his father, a successful electrical engineer—that true improvement requires structure. Reinforcing this quality was his first teacher, Charlie Earp, the head pro at Royal Queensland Golf Club, where Norman was a trainee. Earp had two pet acronyms—DIN (do it now) and DIP (do it properly)—that Norman still lives by. He also says “due diligence” a lot.

Norman needed structure and discipline to make up for not taking up golf until he was 16, a after doctors advised him to give up rugby and Australian Rules football (he had represented the state of Queensland in both) because of some serious injuries to his mouth and jaw. He started by playing with his mother, Toini, a multiple club champion at the Virginia Golf Club in Brisbane, but soon would devote himself more to solitary hours on the practice range.

“I was determined to commit beyond anybody else, and I followed that well into the ’90s,” Norman says. “If I saw somebody hit balls for six hours, I’d do it for eight. Somebody hit 500 balls a day, I’d hit 800. I knew the only way to get ahead of anybody was to work harder than anybody.” Says Wadkins, “Greg had a work ethic that was just ridiculous. In his era, no question he worked the hardest. He earned his game.”

Norman also eschewed shortcuts. Although he won on the Australasian Tour at the West Lakes Classic in only his third professional tournament in 1976 at age 21, Norman decided he needed five years of playing around the world on the Australasian Tour and European Tour before testing himself full time in America. He won 15 times combined on those tours before joining the PGA TOUR in 1983,where he got his first win, at the Kemper Open, the next year.

“Waiting was the best thing I ever did,” Norman says. “I wanted to experience every kind of weather and grass and sand and be comfortable with all the cultural differences.” More than just a long hitter, Norman emerged a well-rounded player. He is particularly proud of his short game, which was heavily influenced by sessions with Ballesteros, a past Memorial Honoree. “Seve was very instrumental in the success of my career,” says Norman. “In my early days in Europe we would play practice rounds, and he’d say, ‘Greg, you drive it so good, show me.’ And I’d respond, ‘OK, but you show me some short game stuff.’ And I’d try to absorb that genius like a sponge. Our relationship cooled in the mid-’80s, but we got closer later on. He’d come to the house, we’d talk about life. My kids loved him. A lot of people didn’t get to see it, but he was such an open guy in so many ways.”

With a blend of both power and touch that has keyed the dominance of greats from Jones to Woods, Norman built a Hall of Fame record. It includes 91 victories worldwide, including 20 on the PGA TOUR, 14 on the European Tour and 31 on the Australasian Tour. His two major championship victories were both virtuoso performances. His consistency at the top allowed him to stay No. 1 in the world a total of 331 weeks, the most of anyone (Nick Faldo is next with 91 weeks) since the ranking was established in 1985 not named Woods.

Beyond the raw numbers, Norman’s best golf was electrifying. He shot more 62s and 63s and 64s on diffcult courses than anyone, even Johnny Miller, many in closing rounds. His record 24-under par performance at the TPC Sawgrass Stadium Course to win the 1994 PLAYERS Championship is the prototype of power golf subduing a harrowingly confined layout.

Norman put together a 63 in the second round of the Open Championship at Turnberry in 1986 on a day when only 15 players broke par, and when only a 3-putt from 28 feet on the last hole kept him from becoming the only player to shoot 62 in a major. At Royal St. George’s in 1993, Norman trailed Faldo by one at the start of the fourth round, but shot a 64, hitting all 14 fairways and 16 greens, to win by two. That round included a missed 18-inch par putt on the 71st hole.

“Anybody who doesn’t believe Greg wasn’t one of the best players the game has ever seen only needs to look at that tournament,” says Butch Harmon, Norman’s coach from 1992 through 1996. “The last round is to this day the best round of golf I’ve ever seen in my life. There was a 25-mph wind that day. Greg never missed a shot, had complete control with every club. That was the perfectionist being perfect.”

The depth of Norman’s reservoir of ability was better appreciated after the 2008 British Open at Royal Birkdale. At age 53, with a game eroded by time, disuse and injury, Norman began as a 500-1 shot at the start of the week. But with inspired play, he negotiated some of the highest winds ever seen at a major championship to take a two-stroke lead into the finnal round. Though he eventually finished third, the performance was a final validation that Norman’s status as a superstar was built more on his game than his charisma.

Not to say Norman wasn’t magnetic. “This sounds crazy, but you could feel when Greg got to the golf course before you saw him,” says Ogilvy, recalling his teenage experiences watching Norman in Australia. “People would be running and you’d hear voices getting louder. You couldn’t help but be drawn into it. It was beyond the golf. This guy who looked like a surfer was more like a movie star. And he’s doing what I love to do, and now I want to be like him. An incredible influence.”

But even if Norman had been a tour clone, his relentless excellence would have set him apart. Using strict comparative performance criteria, Golf World magazine in 2014 ranked Norman behind only Woods as the best player in golf since the PGA TOUR began keeping extensive statistics in 1980, far ahead of next-best Phil Mickelson.

Norman says he got there by not comparing himself. “I really didn’t care about being ranked No. 1,” Norman says. “My goal was always to be the best I could be. Early in my career, I didn’t obsess about the top of the ladder. Instead, in my mind I made the ladder the eternal ladder, right? How do you get to the top? Well, the top is never there.”

Unfortunately, it made for falls from greater heights. And it’s beyond dispute that relative to his successes, Norman suffered more close losses than any great player in history. Competitively, the ledger of fate never came close to evening out.

Norman was most stunned by Larry Mize’s chip-in from off the 11th green at Augusta to defeat him on the second hole of sudden death in 1987 at the Masters, the tournament he most coveted, where he would finish third or better six times but never win. Making it harder to take was that in the previous major, the 1986 PGA Championship at Inverness, Norman had lost when Bob Tway holed a sand shot on the 72nd hole. “The two unluckiest breaks ever in a major, two majors in a row,” says Ogilvy. “Those two chips don’t go in, Greg’s story would be very different, I think.”

Indeed, Tway’s shot came only two weeks a er Norman had won his first major at Turnberry. Because he’d failed to hold 54-hole leads at the Masters and U.S. Open that year (Norman is the only player ever to lead five straight majors—the 1986 Masters to the 1987 Masters—after 54 holes), his victory at Turnberry had augured for a future of majors in bunches. After Norman won at Royal St. George’s, a crushing playoff to lose to Paul Azinger at the PGA Championship (again at Inverness, where Norman lipped out on the 18th hole in regulation and in sudden death), seemed to reverse momentum again.

In the history of golf, no player who got there as often in major championships was ever rewarded less. Norman’s 30 career top 10s in majors—more than contemporary rivals Faldo and Ballesteros—ranks 11th all time. But of the 10 players with more, all have at least seven majors except for Phil Mickelson, who barely exceeds Norman with 31 top-10s, and whose supposedly hard-luck career has nonetheless produced five majors.

In all, Norman held the fourth-round lead or a share of that lead in 14 majors— the Masters in 1986, 1987, 1989, 1996 and 1999; the U.S. Open in 1984, 1986 and 1995; the British Open in 1986, 1989, 1993 and 2008; and the PGA in 1986 and 1993. The first 14 times Tiger Woods had the lead or a share in a major on Sunday, he won all 14. The eight times that Norman shared or had the 54-hole lead alone, he only won once. In evaluations that judge the historical signi cance of players by their number of majors, Norman suffers the most. It’s hard not to conclude that he didn’t underachieve.

“If Greg had won three or four more majors, I think history would recognize him where he should be recognized,” says Ogilvy, whose admitted national bias is off set by his astute grasp of golf history. “But unfortunately, we all get the blinders on about majors in golf, where they become the only things that really matter. Which isn’t true. But because Greg won only two majors, he goes next to all the guys who won two majors. Which is not even close to right. To me, the incredible quality of his golf over a very long time should give him the equivalent status of a 10-time major winner. But it doesn’t work that way.”

Norman admits to his share of dark nights of the soul, but a er reconciling the pain of his loss at the 1996 Masters, where he entered the nal day leading by six but would lose on an excruciating Sunday to Faldo, he resolved to look on the bright side. “My best memory of my career is the resiliency of me,” he says. “Resilient because some of the stuff that happened to me hasn’t really happened to any other individual in the game’s history. But I put my blinkers on and kept going.”

At the same time, he has ruminated on what might have been missing. Vulnerability under pressure is a tough subject with any professional athlete, but especially the very best. Norman acknowledges that he wasn’t su ciently ironclad at winning time.

“It’s funny about pressure, because people often assume I didn’t welcome it,” he said in 2011. “In those situations … I liked it for some stupid reason. But, obviously, the recipe wasn’t quite right. I’ve analyzed it, big time, and I see more now. Because I’ve opened myself up to the realization that I wasn’t perfect, even though for so long I tried to be perfect and was sort of blinded by fear of failure to admit flaws. I’ve opened myself up to admitting I made mistakes. I still became the No. 1 player in the world for other reasons, but I did some things wrong.”

According to Harmon, “Greg had a tremendous amount of guts. He wasn’t afraid of any shot, and that was one thing that hurt him, especially in majors. You can’t be that aggressive in majors all the time and get away with it.”

Norman doesn’t disagree that he “lived by the sword and died by it,” and sees the reason as the flip side of the independent mind that was vital to his greatness. “My biggest mistake in my golf career was thinking I could do it myself,” he says. “I was so determined to do it Greg’s way, I was detrimental to myself. I truly believed in myself so much, but sometimes that total belief can misguide you, your biggest strength becomes a liability, and you become your worst enemy.”

Norman now believes he should have been more open to advice from others and employed a full-time sports psychologist, trainer and masseuse. But a traumatic event early in his career made him wary of the judgment of others.

“I lost all my money in the early ’80s through some bad management, and I’ve never forgotten,” says Norman. “And then I had problems with the Australian taxation office. Bank accounts parked around the world, that I thought were fine but weren’t. Just as I hit No. 1 in the world in 1986, I had to do a massive amount of unraveling. So I became very guarded the rest of my life. Even to this day, in a business situation, my antennae can go up, and I won’t trust.”

Norman has come to see that the roots of being a lone wolf were sown in an emotionally distant relationship with his father, Merv Norman, a stern man whose high expectations restricted the flow of compliments to his only son. He disapproved of Greg’s decision to pursue a career in golf, recommending instead that he join the Royal Australian Air Force and train to fly F-111 fighter jets.

“My father and I, we had a father-son relationship, but we didn’t have a father-guidance relationship,” Norman says. “But I saw his parents and the way they were with him. It was tough love, but I didn’t really understand that at the time. After I turned pro, especially as an international player, with just your suitcase, your clubs and your briefcase, you have to build this tough outer layer. I would have loved to have been able to say, ‘Hey dad, can we have a beer? I need to tell you about this.’ But it didn’t happen that way in my world.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, the two grew closer as Norman’s competitive career waned. “Once I stopped asking myself why we weren’t closer—because there was really no answer—it was better,” he says. “And I have a great relationship with my dad now. He probably still thinks he was right, but for the last 15 years or so, we can talk about what we went through with each other.”

Norman doesn’t deny that his desire to prove his worth to his father provided immense fuel for his exploits, and his own son, Gregory Jr., agrees. “Probably my dad’s relationship with my grandfather got him to No. 1,” says the younger Norman, who runs a wakeboarding park in South Carolina in partnership with his father. “Because he wanted to prove to him that he could do it.” Norman doesn’t disagree, but also says, “As I told Gregory once, ‘I want to break the chain.’ So when he accomplishes something, I give him a huge hug and say, ‘I’m so friggin’ proud of you.’”

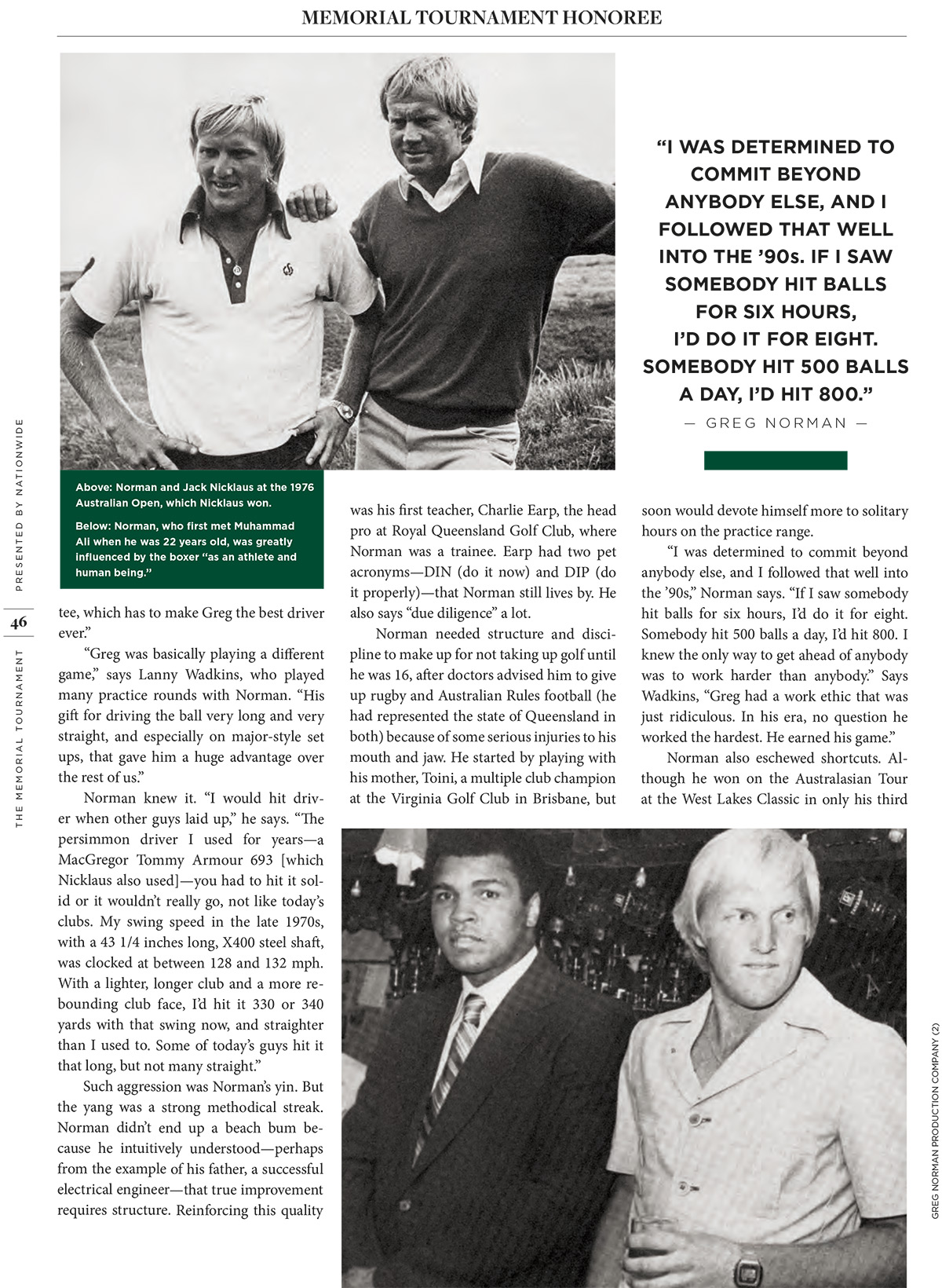

One of the few people Norman did trust was Nicklaus. It began when he made Golf My Way, written by Nicklaus in 1974 with Ken Bowden, the foundation of his fundamentals. After Norman got his first victory, by five strokes at the 1976 West Lakes Classic, organizers paired him with Nicklaus in the Australian Open the following week. With his blond hair and big game, Norman was hyped by the Australian golf media as “the Bear Cub.”

“When somebody on Tuesday told me I’d be paired with Jack, I was a bag of nerves,” Norman says. “The first tee at The Australian is elevated, and because of Jack, the fairway was lined with people. I had to take a deep breath just to get the ball on the tee, but I had no chance and cold topped it. The ball skimmed a low bush in front of the tee and went no more than 60 yards, and only because it was downhill. Total silence from the gallery. I shot 80 that day.”

After he recovered with a second-round 72, “Jack sat down next to me on a bench in the locker room, told me he was impressed with my game and my demeanor, told me I should play in America, and slapped me on the leg. That was a bolt of confidence.”

Nicklaus gave more than encouragement 10 years later after the third round at Turnberry, with Norman holding a one-stroke lead. In the hotel dining room, Nicklaus approached Norman’s table and asked if he could offer some advice. “I knew Greg hadn’t fonished it off on Sunday at the Masters or the U.S. Open,” Nicklaus remembers. “I had seen that under pressure he had a tendency to push the club outside on the takeaway and get laid off, causing a push to the right. I told him, ‘You have a fault in your swing that I think you can correct with a conscious effort that isn’t going to bother you.’” The easy fix was a reminder to keep grip pressure light in the last round, which Norman said he consciously did. “Whether I had any influence on Greg winning or not, maybe I did,” says Nicklaus. “He seems to think I did. And so that’s nice.”

Norman’s favorite conversation with Nicklaus came before what he calls his fondest victory, the 1992 Canadian Open, which broke a 16-month winless patch in which Norman said he had lost his enthusiasm for the game. Along with a continuing series of tough losses in majors, Norman in 1990 had been beaten by a holed 7-iron for eagle on the 72nd hole by Robert Gamez at Bay Hill, and a holed 40-yard sand shot by David Frost on the 72nd hole at New Orleans.

“I was lost, so I called Jack up, and he said to come over. He was outside in his driveway when I arrived. So we stood there by my car, talking for a long time, about stuff like when he went through his slump, how he got out of it, what I’ve got to work on, am I digging in the right place, and how deep do you dig. He also talked about when you’re at the top, people want to beat you, and they might do something extraordinary to beat you, and that you have to accept that. We got so engrossed that it started raining and we didn’t notice until we were soaking wet.

“From there I drove to Old Marsh, where I practiced. Before I got in the gate, I pulled over on the side of the road. It had stopped raining, so put the roof down on my convertible, put the seat back, looked up at the clouds and asked myself a simple question, ‘What’s wrong with your game?’ And the answer came back: ‘There’s nothing wrong with your game. But there’s something wrong with your attitude.’ I realized that I was foggy because I had created my own fog. I went to the driving practice range and came off a totally new golfer. And I went to Canada and won.

“The point is, Jack opened my mind up. Jack really was great at giving a message by allowing you to think about it, and let you learn in our own way. He understood me.” Says Nicklaus, “I always knew Greg would have great success, and I enjoyed encouraging him. A lot of things we talked about over the years he used in his life and the way he did things. I think he does things in a lot of ways better than I have.”

As he’s gotten older, Norman has been more open to searching within. Every two years, he and his wife go on a trip to a place they’ve never been. Last year, it was the Kingdom of Bhutan, high in the Himalayas. “Kiki picked it,” says Norman. “Somehow, she knew it would be good for me.”

At the swift confluence of the Pho Chhu and Mo Chhu rivers, Norman entered the “Palace of Great Happiness,” a 17th century architectural marvel of gold pillars and hand-carved wood where Bhutan’s kings are crowned. The sensation he experienced was so moving that, on the ight home, he wrote a six-page entry in his journal, which said: “As I stepped inside the Kuenray room and the throne of Je Khenpo, I was awestruck by what my eyes, then soul, absorbed. So incredible, so magnificent, so captivating. My body experienced for the first time ever, 100 percent eruption of goose bumps from head to toe. Just this one moment was enough to make our trip to beautiful Bhutan worth every second.”

“It definitely changed me,” he says. “Now when I’m driving in traffic, and I get a little impatient because I have to get somewhere, I actually go back to that moment. It’s stayed with me, and I am different.”

Perhaps. But before his visit to the palace, Norman had strapped himself into a helicopter that rose to 20,000 feet for a spectacular aerial tour of Mt. Everest. “It was crystal clear, and if it hadn’t been for very strong winds we would have gone higher,” he says. “What was I thinking? That I want to climb that mountain. And I believe I still can. We’ll see.”

Would reaching the summit be the ultimate moment? Probably not. Remember that for Greg Norman, who never stops climbing, the top is never there.